I’ve had several readers over the past several months ask me to comment on a post authored by Chuck Missler entitled, “Meanings of the Names in Genesis 5.” The essay puts forth the idea that the list of names in Genesis 5, stretching from Adam to Noah, can be read as though the writer intended the string of names to describe the gospel story:

| Hebrew | English |

| Adam | Man |

| Seth | Appointed |

| Enosh | Mortal |

| Kenan | Sorrow |

| Mahalalel | The Blessed God |

| Jared | Shall come down |

| Enoch | Teaching |

| Methuselah | His death shall bring |

| Lamech | The despairing |

| Noah | Rest, or comfort |

To be direct, this conclusion doesn’t follow from the data. That is, it’s a non sequitur. The reason is that both the approach and the data are problematic.1 The goal of using this analysis as some sort of proof for a “cosmic code” is also untenable.2 I’ll briefly explain why as we progress, limiting myself to the problems that are best translatable to this environment and audience (that is, there are more problems that require reading Hebrew and being able to show Hebrew, the latter of which I still can’t do in the blog — I can’t even get the transliteration to show correctly, and so the “single-quote” mark used for Hebrew aleph gets turned around – sorry for that, but nothing I try works).

The Methodological Problem

Missler writes in his beginning:

Since the ten Hebrew names are proper names, they are not translated but only transliterated to approximate the way they were pronounced. The meaning of proper names can be a difficult pursuit since direct translations are not readily available. Many study aids, such as conventional lexicons, can prove superficial when dealing with proper names. Even a conventional Hebrew lexicon can prove disappointing. A study of the original roots, however, can yield some fascinating insights.

The flaw here is a failure to honor the writer’s context and intent. If it is true that the names in this genealogy are proper names, then THAT is how the writer wanted them understood. As we have seen with our discussions of ‘adam, a writer can do things (like add the definite article) when he wanted readers to discern that the term wasn’t a proper name, or let the reader think about more than one option by making the term ambiguous. Conversely, when a proper name was the intent, one would remove the definite article to telegraph that meaning was intended. Missler’s take suggests the writer wanted to hide information (encrypt this “code”). Why the NT writers couldn’t figure this code out and then use it as a proof for the messianic nature of Jesus isn’t explained by Missler. A critic could read him as saying he’d figured out something in the text that Paul (or Jesus) couldn’t, since they never bring it up — which is (I hope) something Missler wouldn’t want to say, as that would amount to a claim of new inspiration. But that’s a problem for all this “code” thinking.

Further, that a “root” might mean something is itself problematic. Many words share common consonants (the “root” or base), but that doesn’t mean all the words that share those consonants have a shared, basic meaning. This thinking is known by scholars and those engaged in serious exegesis as the root fallacy. It isn’t hard to show that it’s a bogus approach to understanding words. For example, suppose I try this in English. Do the following words, all of which share common consonants, really all have some meaning that unites them?

BuiLT

BeLT

BoLT

BLoT

Seriously? Not only is this approach fallacious, but (I hope) it serves to make the point that words only have meaning IN CONTEXT. That is, although you can have three or four words that share a root, they actually don’t “mean” anything (much less share a common meaning) until they are put into a clause or sentence by a writer — a placement that gives the words a grammatical and literary context (when that sentence is considered in light of surrounding sentences, paragraphs, etc.). Words by themselves mean nothing, and so roots of words by themselves mean nothing. And in our case, a writer chose to create a genealogy (there’s the genre / literary context), and so he chose proper names (that’s what goes into a genealogy) and so we can be sure that the writer meant these names to be understood as, well, names.

But Mike (you might object) what about the divine author? He might have meant more! Sure, and if he did, he would have told Paul or some other NT writer under inspiration, so they could have revealed the encrypted prophecy. Do we really want to think God saved that for Chuck Missler? This is what I mean about how these codes can really get you into theological trouble. Now, I don’t think for a minute Chuck Missler wants to go there, but that’s the logic chain, and it’s easy to follow. And just why would God want a prophecy encrypted anyway, when so many other prophecies are fairly transparent — including prophecies about a messiah?

For those interested in words and how they work, including the root fallacy and other fun fallacies, I recommend the following books:

Biblical Words and Their Meaning, by Moises Silva

Exegetical Fallacies, by D. A. Carson

Linguistics & Biblical Interpretation, by Peter Cotterell

The Etymological / Philological Problems

Now for the specifics.3 Let’s take the names one by one.

Adam

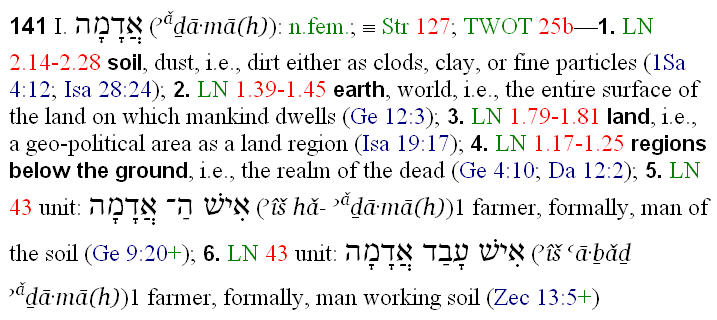

Missler writes: “The first name, Adam, comes from adomah, and means “man.” As the first man, that seems straightforward enough.” Well, it actually isn’t, as Naked Bible readers know by now. First, the name “Adam” does not “come from” the word ‘adamah (Missler misspells it as adomah, with an “o” vowel, or his source did). The word ‘adamah means “ground” or “land.”

Adam” as a proper name comes from ‘adam, which, as we have seen in earlier posts, can mean “human, humanity, man” or the proper name, “Adam.”4

Seth

Missler says that Seth’s name means “appointed.” This is a possibility, though Hebrew and Semitics scholars disagree. Wenham’s comment is representative:

Though Eves explanation of Seths name suggests it is derived from the verb shiyt/siyt (to place, put) there may be no etymological connection, simply paronomasia.5

If Seth does derive from this Hebrew verb, since the term refers to an object (a person) it would actually be better translated “substitute,” not “appointed” as Missler suggests.

Enosh

Missler writes:

“Seth’s son was called Enosh, which means “mortal,” “frail,” or “miserable.” It is from the root anash: to be incurable; used of a wound, grief, woe, sickness, or wickedness. (It was in the days of Enosh that men began to defile the name of the Living God).

The statement is odd. There is no Scripture citation that in the days of Enosh people began defiling God’s name. I’m guessing that he means Gen 4:26, which most Bibles have as: “At that time people began to call upon the name of the Lord” (ESV). Missler thinks that a mistranslation, but it isn’t. The difference between that translation and having the verse say that “people began to defile the name of the Lord” is due to the first of two verbs in a sequence being a Hebrew homonym. Like English, Hebrew has distinct words that are spelled exactly the same way but are divergent in meaning (e.g., “lead” [the verb] and “lead” [the metal] — and think of how that also muddies the “root” idea discussed above). To illustrate:

Since Hebrew moves from right to left, one cannot cheat and translate the two as “began to defile.” Not only is “defile” the (potential) first word, but the second one “to call” is quite clear (and has the infinitival lamed prefix). And so, you either go with “began to call” or “defiled to call.” I think the first option makes better sense (the latter really makes no sense at all).

But all that is actually beside the point. Does ‘enosh mean “mortal, frail, miserable”? The word ‘enosh means “man” or “human.” This is clear from its scriptural use, where it is commonly occurs in poetic parallelism with ‘adam. A meaning of “mortal” can work here, so I don’t have a problem with that. But the idea that ‘enosh “comes from” a root that means “mortal, frail, miserable” is not correct. That idea comes from a different word, ‘enush. Transferring meaning from one to the other is to commit the root fallacy.

Kenan

Missler writes:

Enosh’s son was named Kenan, from which can mean “sorrow,” dirge,” or “elegy.” (The precise denotation is somewhat elusive; some study aids unfortunately presume an Aramaic root synonymous with “Cainan.”) Balaam, looking down from the heights of Moab, employed a pun upon the name of the Kenites when he prophesied their destruction.

This is another odd description. First, Aramaic has little to do with seeing this name as “Cainan.” The fact is that this name is spelled qynn, the first three consonants of which are identical to qyn (“Cain”). The Septuagint transliterated the name as “Cainan.” The only difference in the consonants (Hebrew originally had no vowels) is the final “n”. Scholars disagree on its role in the name. Some take it as a diminutive (in which case it would be an appendage that means “little,” and so “little Cain” would be the meaning). There is precedent for an “n” diminutive in biblical Hebrew, but scholars have not found the argument compelling enough for consensus. And the option invariably takes us into the issue of whether the genealogies of Gen 4 and 5 came from a single source or not, which is well beyond the scope of what we’re doing here. Another option is that the final “n” is (in academese) “hypocoristic” (a term that in effect means “it’s a nickname for Cain”). I have no idea what Missler is angling for in the reference to Balaam. I suppose that he wants to connect the spelling of qynn with qyny (“Kenites”), but that wouldn’t explain the final “n” anyway. And what Balaam was doing isn’t of value for what the writer of Genesis 5 was doing when writing a genealogy. The contexts are entirely different.

The fact that no one is really sure how to take the final “n” also points to the fact that no one really knows what the term would mean *if it were not a proper name*. Missler’s suggestion (he gives no source) apparently comes from taking the meaning of the noun qynh (an altogether different word) and transferring that meaning to this name. Again, the root fallacy raises its head.

Mahalalel

Missler writes that the name “means ‘blessed’ or ‘praise; and El, the name for God. Thus, Mahalalel means ‘the Blessed God’.” This rendering is scarcely possible in light of Hebrew morphology. The verbal root is h-l-l, and does mean “to praise.” The prefixed “m” indicates that this form is a participle (unlike the other examples he gives). That means “El” (“God”) is its object. The name means “praising God” — which does not fit at all with Missler’s allegorical interpretation of the sequence.

Yarad

Scholars would agree with Missler’s note that this name has the same consonants (y-r-d) as the Hebrew verb yarad (“to go/come down”). The problem here is that this is a proper name. That the consonants are the same does not prove that the meaning of the verb with the same consonants is to be transferred to the name. A convenient modern parallel is illustrative: are we to assume that RUSH Limbaugh’s name “means” to hurry? Or should RUSH be understood as “a tufted marsh plant,” or perhaps “a fraternity’s recruitment tradition”?6 I hope you get the point. The meaning is therefore uncertain. Other issues contribute to this uncertainty. First, the same consonants occur in 1 Chron 4:18 (also a genealogy) vocalized as Yered. Second, the consonants, if understood verbally, could also be translated as a command “Go down!” Third, Akkadian parallels to the term suggest a meaning of “slave” or “servant,” though not all scholars accept those parallels as decisive here (See Hess’ book in footnote 5, pp. 69-70).

Enoch

Missler notes that Enoch (spelled with consonants ch[h-dot]-n-k) means “‘teaching,’ or ‘commencement’.” This is a bit misleading in that he gets each meaning from a different word (or, at least that is the case with respect to the Semitic data).The two possible roots are also technically not in the same language, though they are both Semitic. There is a Hebrew verb ch-n-k that means “to train up, dedicate,” and a West Semitic verb of the same spelling that means “to introduce, initiate.” That the latter and not the former (the choice of Missler’s allegorical string) may be the best option here is suggested by the context of the same name in Gen 4:17, where Enoch was the first offspring of Cain, and the namesake of the city built by Cain. Now, if it be presumed that this was the first city, then the “initiate” meaning would go much better as a meaning. Since no other cities are mentioned in Genesis prior to this one, it appears that the writer is casting this city as the first one built. There is no rationale I can see, other than to make the allegory “work,” for Missler to choose “teaching” over the other. At any rate, it’s far from secure.

Methuselah

Missler writes:

Enoch named his son to reflect this prophecy. The name Methuselah comes from two roots: muth, a root that means “death”; and from shalach, which means “to bring,” or “to send forth.” Thus, the name Methuselah signifies, “his death shall bring.”

This is incorrect. Although Missler has a footnote for this claim, the sources are not Hebrew scholars, hence the error. The first part of the name is the problem. Hebrew scholars know that the first part of the name is not muth (more properly, moth, if the meaning would he “death”), but rather Hebrew mt (“man”; this lemma occurs just over 20 times; see e.g., Deut 2:34; 3:6).7 That mt and not an original muth/moth is the first part is known because of rules of Hebrew orthography (“spelling”) and vowel reduction. An original “historically long” vowel such as required by muth/moth will not reduce to shewa, as it is in the Hebrew text of Methuselah’s name.8 The meaning of Methuselah’s name is therefore “man of sh-l-ch.” Missler assumes the second element is a verb, but there are actually a number of translation options, since there is more than one sh-l-ch in biblical Hebrew (and wider Semitic). The most plausible is “weapon, spear” (see this sh-l-ch in Joel 2:8; Neh 4:17; 2 Sam 18:14). The name “Methuselah” would then mean “man of the spear” (i.e., “warrior”). Other scholars see a reference to a river sh-l-ch or a deity by that name. The one thing it cannot mean is what Missler suggests.

Lamech

I have to be honest. The treatment of this name is egregious. Though I appreciate Missler’s wide influence as a catalyst for people to get into the Bible, what he does here would get him in serious trouble in a hermeneutics or exegesis class, much less a Hebrew class. Missler elicits a meaning for this name on the basis that it sounds like an ENGLISH word (“lament”)! He writes:

Methuselah’s son was named Lamech, a root still evident today in our own English word, “lament” or “lamentation.” Lamech suggests “despairing.”

No language in human history can be interpreted this way. Just because a Chinese word might aurally sound like a word in my language (or any other language) doesn’t mean it shares the same meaning as the word from the other language!

It isn’t hard to show how deeply flawed this idea is. Anyone who has studied another language besides their own knows that the new language has similar sounding words or vowel-consonant combinations to words in their native language, and yet there is absolutely no relation in meaning. Put bluntly: Hebrew and English are not the same language. But for those to whom that isn’t obvious, let me illustrate.

Consider these three Hebrew words: yam, sod, regel. Do they really correspond to English words for “sweet potato”; “dirt”; “to squirm”? Hardly. They mean, in order, “sea”; “council”; “foot/leg.” I could provide hundreds of examples from a range of languages to demonstrate the absurdity of this approach. Anyone who has studied a language other than English could also contribute their own list.

I should add that the Hebrew word translated “lament” is qiynah. No aural resemblance to Lamech.

The reality is that Lamech has no known, certain “meaning” so far as scholars can determine. Here is a sampling of the speculation:

Like Abel for hebel, Lamek is the pausal form of Lemek, but unlike Abel, not certainly of Hebrew derivation. It may be connected with Sumerian lumga, a title of Ea, as patron deity of song and music, but this is very doubtful. Other suggestions based on Arabic include strong youth or oppressor.”9

Noah

This name is well understood. It means “rest” as Missler notes.

Conclusion

So where does this leave us? It quite clearly means that Missler’s allegorical “sentence” or prophecy (or “code”) in Genesis 5 is bogus.

I hope readers see the larger point, however. WHY would God want to encrypt a message that is found elsewhere plainly in sight? The whole idea makes no sense. Frankly, if we need these sorts of “codes” to stimulate us to believe that God was capable of prompting men to write down revelation for human posterity, there’s a serious problem with our faith and theological thinking. If one believes in God, and that such a God can do something as simple as prompt humans to write something down, and then further prompt them to preserve it, inspiration doesn’t need some magical justification. It’s a simple, reasonable idea.

- Let me say that, while I think Missler’s essay is misguided and deficient in terms of understanding Hebrew grammar and philology, Missler is to be commended for prompting so many lay people to get interested in studying the Bible. I personally know a number of people whose interest in Scripture is directly traced to Missler’s influence. ↩

- Many readers will know what I think of Bible codes in general. The idea that the Bible has embedded codes that somehow escaped the attention of inspired OT and NT authors when they themselves comment or quote the Bible is, to say the least, theologically troublesome. The goal of inspiration / producing the Bible was clear communication, not encryption. Every code argument I’ve seen fails to consider the multiplicity of manuscript data, which goes far beyond differences in words. Rather, it extends to phrases and arrangement (micro and macro) of large blocks of Scripture content — e.g., differences between LXX and MT. ↩

- The screenshots come from Logos Bible Software’s Dictionary of Biblical Languages: Hebrew. For readers who know some Hebrew and can follow transliteration, I recommend Richard Hess’s scholarly work on this subject: Studies in the Personal Names of Genesis 1 to 11

. ↩

- Incidentally, ‘adam is one of several words that share the root consonants: ‘-d-m (aleph, daleth, mem). Others include ‘edom (red, Edom – Edom had reddish dirt) and ‘adom (the color red or blood — but of course not all things that are red have anything to do with blood). And for those familiar with my critiques of the ancient astronaut nonsense of Zecharia Sitchin, please note that the Sumerian scholar A. W. Sjoberg (he was professor of Sumerian at Penn when I was there) notes that Sumerian á-dam is not actually Sumerian; rather, he demonstrates that it was brought into Sumerian after being *borrowed from* Canaan! See A. W. Sjoberg, “Eve and the Chameleon.” Pages 217-225 in In the Shelter of Elyon: Essays on Ancient Palestinian Life and Literature in Honor of G.W. Ahlstrom (W.B. Barrick & A.R. Spencer, eds.; Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1984). ↩

- Gordon J. Wenham, vol. 1, Word Biblical Commentary: Genesis 1-15, 115. The word “paranomasia” is a literary term for word play. Wikipedia: “a form of word play which suggests two or more meanings, by exploiting multiple meanings of words, or of similar-sounding words, for an intended humorous or rhetorical effect.” ↩

- Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 2003. ↩

- See Hess, Studies in the Personal Names of Genesis 1-11, p. 70; Wenham, Genesis 1-15, Word Biblical Commentary, p. 128; Sarna, Genesis; Jewish Publication Society Commentary, p. 43; Hamilton, Genesis 1-17; New International Commentary of the Old Testament, p. 258. ↩

- See Jouon-Muraoka, Grammar of Biblical Hebrew, Sec. 29b. ↩

- Wenham, p. 112. The Arabic term alluded to by Hamilton would be yalmak, “powerful man”. ↩

Y’know, in the past, I enjoyed the work of Chuck Missler, in terms of making the Bible more interesting, etc. Part of this was likely speculative and sensational, and for those folks who study the Scripture more in depth due to his work, it’s probably been a blessing.

But as I understand original languages more, and deeper themes in Scripture, I begin to see how shallow many of these studies and Bible teachers are, without understanding the languages, or deeper themes. In some ways, one could say, “if only it was about a person reading their Bible,” when it comes to something “simple” like initial salvation (i.e., only coming to Christ). But to grasp the larger picture and greater context, much more is needed. These days, it’ll be either coming to you framed by a theological /denominational tradition (with its inherent biases and prejudices), or a non-denominational version of the same (with different “flavors”). Or, in flavors of “left” and “right”, or…whatever, really, there’s no end. Oy…

Thanks for this. I kind of feel sorry for Missler, when word gets back to him about this. Hopefully, it’ll be a benefit to him to learn what Scripture is actually saying (or not saying), as much as it does us.

I’m typically averse to comment on the work of people who mean well, and have been used by God in a positive way, such as encouraging personal Bible study. But I’ve gotten this request so often (a spurt recently) that I’m tired of not providing an answer. I’m not sure why that particular essay draws so much attention. Missler is a smart guy, a conclusion anyone could draw reading his resume, but he lacks real training in biblical languages and a number of areas of biblical scholarship. But to his credit, I don’t think he claims to be what he isn’t in that regard, and has had a positive impact on people.

Ah, thanks! I wanted you to do this three years ago when I was still listening to Missler’s commentaries.

Chuck certainly means well in every shape and form. He knows he is not a scholar and states so many times. He describes himself as a Bible expositioner; and so, he produces expositional commentaries. He often used to say (and still says) not to believe everything he says about the Bible. He knows and says that good scholars are often divided on many issues, and that he presents what makes most sense to him based on his hermeneutics and exegesis.

You have to commend him for that.

“Im typically averse to comment on the work of people who mean well, and have been used by God in a positive way…”

Why? The church is better off with someone correcting its member’s homework. Anyone (even Ken Ham!) can be used by God. God gave you linguistic gifts that others don’t have. You need to do this more often, not less.

Okay; consider me rebuked. I have no trouble going after hucksters, but it’s tough when it’s someone who means well. I don’t want to be *that PhD guy* (the one who beats up on people who don’t have the same training). Maybe it’s my blue collar background.

Great post would like to see you tackle some more of this type with logic and grammar. I also agree with your bullet point number 1…Mr Missler is thinking outside the box and exploring the word where no others are going and he is not afraid to let scripture speak for itself, he may not be correct in all his theories but for sheer non-conformity and dedication to the Word he has my respect.

Yes; you have to appreciate the willingness to call things as you see them.

Well said by both Kenneth and Mike. I recently watched a Missler teaching and noted how he sort of off-handedly refers to either himself or Hal Lindsey as scholars and how they discovered such and such in the bible. I thought that comment was going a bit far.

One thing he said in another lecture was that the more he studies the bible, the older he gets, the more real and fantastic it becomes to him. I agree with that. On the other hand, he comes across sometimes as the one who discovered deeper truths or alternative approaches to certain doctrine or ideas that are found in the texts. Then I’ll find that very similar teachings are espoused by others or have been around for many years prior to Missler coming out with it. I can’t tell who’s copying who. But its just the way he comes across, not giving credit to anyone else when due.

Mostly I want to say here, thanks to Mike for all this work and that this kind of rebuttal teaching is very important for some of us.

I think these observations are valid, but my general impression is that, for the most part, Missler isn’t pretending to be what he’s not. I hope that’s accurate.

Umm. It depends if what you are referring to is a new commentary or briefing pack vs an older one (from the 90s). I’ve listened to both his old and new commentaries on Gen, Ex, Num, Dan, Matt, 2 Pet and Jud, and others, as well as many of his briefing packs all throughout 2005-2008, and most of the time he does credit others for “discoveries” in the text. He may not have done it everytime, but I think we can all be guilty of that at some point, when we see something that someone else brought up but we still present it as if we discovered it. I don’t think it is always innapropriate.

Ditto re: Missler’s heart vs tactics [and the need to feed the family].

I thought I was ‘done’ with this topic a long time ago, and to that point:

MSH – I pray that this excellent article becomes the gold plumbline by which other diatribes on this topic are assessed, henceforth.

While your exposition of the individual names is very thorough and sufficiently undermines Missler’s thesis, I do have to take some issue with your initial rebuke:

“The flaw here is a failure to honor the writers context and intent. If it is true that the names in this genealogy are proper names, then THAT is how the writer wanted them understood. As we have seen with our discussions of adam, a writer can do things (like add the definite article) when he wanted readers to discern that the term wasnt a proper name, or let the reader think about more than one option by making the term ambiguous. Conversely, when a proper name was the intent, one would remove the definite article to telegraph that meaning was intended.”

Are we, as readers, supposed to take the names Touchstone, Pandarus, Pinch, Elbow, Mistress Overdone, Quince, Snug, Bottom, Flute, Snout, or Toby Belch as merely proper names when we are reading our Shakespeare? Or, within the context of the ancient world, there is Oedipus (“club-foot”), Prometheus (“fore-thinker”), Paulus (“shorty”), and Jesus (Yeheshuah – “YHVH’s salvation”). Given the commonality of using suggestive names throughout the history of literature, it would be very unwise to discount possible connotations out of hand. Several millennia of very detailed Jewish scholarship on the correct meaning of Adam in the Torah should underline that point.

If those names were in genealogies, I’d suspect Shakespeare intended them to be read as real people (and some real people that could have been known to readers by such names). I guess you need to convince me that when a writer puts a name into a genealogy he doesn’t want readers to think of real people and real generations, but abstractions.

Hi Michael,

Not that I know any Hebrew, but it’d seem you’ve done a pretty good job of refuting Missler’s claims about the meanings of the ten names in Gen 5. Regarding the name “Methuselah” though, I read a link a few years ago (http://creation.com/biblical-chronogenealogies) where Jewish Christian scholar Arnold Fruchtenbaum made the following argument about the meaning of that particular name:

“The name Methuselah could mean one of two things. Therefore, it will either mean man of the spear or when he dies it shall be sent. The debate is not over the second part of the word which, in Hebrew, is shalach; and shalach means to send. While the concept of sending is the primary meaning of shalach, it has a secondary meaning of being thrown or cast forth in a context where the sending is with heavy force or speed. On that basis, some would conclude that shalach would mean either missile or dart or spear. However, that is a derived meaning because the primary meaning of shalach is to send, as any lexicon shows.

Ultimately, how one deals with shalach depends on how you deal with the first part of the word, which has the two Hebrew letters spelling mat. Based upon the root, then the meaning would indeed be man. Hence, commentaries conclude that it means man of the spear or man of the dart. However, the use of the term spear or dart is not the meaning of shalach in any lexicon that I know of. It is simply a derived meaning going from sending to throwing to trying to make a specific object. If mat was intended to mean man, if one was to keep it strictly literal, it would not mean man of the spear or man of the dart, but a man sent.

The second option for mat is that it comes from the root that means to die. Furthermore, the letter vav between mat and shalach gives it a verbal force. That is why I prefer to take it strictly literally, using the root to die and literally it would mean he dies it shall be sent.

I prefer that translation of the name, when he dies it shall be sent, for two reasons. The first reason is that I find it fitting the Hebrew parsing of the name much better. Secondly, it is better in the wider context since, if we follow the chronology of Genesis, the same year he died was the year of the flood. I do not think this was purely coincidental.”

What do you think of Fruchtenbaum’s argument?

It’s wrong to assume shalach means “to send” since that ASSUMES the verb, and not the noun, is meant. That is simply a guess or choice. Nothing drives that conclusion.

Any Hebrew lexicon will note that shalach can be a verb or noun (same consonantal spelling). Did you look at the examples I listed for the noun?

I did look at those verses on blueletterbible.org (I presume there are better lexicons I could’ve checked) and indeed they point out that shlach is a noun in those verses you cited. What I don’t get is how does one know in Hebrew whether a given word is being used as a noun or verb? I’d presume (and, as I say, I don’t know Hebrew at all – which is why I probably should not have commented) it has to do with whether a given sentence makes more sense if shalach is read as a verb or a noun? If so, how do we choose which way is the correct way to go when shalach is being used in a name like Methuselah?

The noun uses of shalach that I listed in the post cannot be taken as a verb. That tells the reader that sh-l-ch must be a noun. The same noun occurs in other Semitic languages.

I apologize in advance if this has already been addressed, but since we are dealing with ancient names is it possible that the proper name came first and the meaning around the word was formulated based on a characteristic of the individual? I guess this is a chicken or egg question, which came first the word that the name is supposedly derived from or the name itself? Like we can sometimes use the word “Einstien” as an adjective to describe somebody who is very intelligent, thousands of years from now scholars might read some literature and derive that the Einstein means intelligent and assign that meaning to the proper name of Albert Einstein.

Or Joe Einstein or Sarah Einstein and somehow determine that all of these people had super intelligence, when in reality the meaning came from one particular individual who had a unique characteristic that distinguished him from everyone else.

I’m not sure what the point would be, as any meaning for any name, regardless of when assigned, still needs to be coherent with respect to the rules of the language.

Do names have meaning today? Some yes other no, when my wife and I named our children we were very particular about what the names meant, but there are some names people have today that are just made up words or at least appear to be made up words. Lets say there was a child born and he was named XYZ, a word with no apparent meaning. Well when this child was 10 years old the child was seen talking to an angel. His name, XYZ, then became defined as “one who was seen talking with angels at age 10” so then from XYZ sprung the verb xyz meaning “talks with angels” and the noun xyz meaning “one who talks with angels”, neither one of these words fully capturing the meaning of XYZ. How do we know that the meaning did not originate with the name and other words derived their meaning from the name rather than the other way around. If that is the case, could it not be true that the rules are diminished?

The issue isn’t whether names have meanings; it’s twofold: (1) getting the meanings right, and (2) the idea that the list of names was designed to transmit the gospel. The fact that there are clear errors in the first part makes the second bogus.

I guess the point I was trying to make does not coincide with either of these two issues. I was just wondering if there is a way to determine what came first. The point I was attempting to illustrate is that if the name came first and words derived their meaning from the name, then the name itself would be the most complete definition because all subsequent words that sprung from the name would be truncated. Back to my Einstein example, we wouldn’t say “that Albert Einstein he sure is a real Einstein”. Though Einstein is used as an adjective to describe somebody who is smart it would by no means capture the entire essence of the man Albert Einstein. So rather than continue to ramble on incoherantly I guess my question would be, if we can’t determine which came first shouldn’t the context in which the name is used be much more heavily weighted in the determination of meaning? Especially in the first occurance of the name?

I am having trouble seeing why the question has any relevance to the post. What we have is the text. Missler at points bungles the meaning of the names, rendering his “sentence” implausible. Maybe I’m not catching what you’re focused on.

Mike, I sure do respect you you. You have laid bare a number of questionable things for me. If only everyone would stick to their area of expertise. 🙂 Poor Chuck has come under the crosshairs of some discernment ministries lately. They are not being very kind to him. I love Mr. Missler but he wouldn’t be in this situation if he hadn’t ventured into some questionable areas……

Sad, but not terribly surprising, as it happens with unfortunate frequency. Glad the site is useful for you!

Most devious is the heart; It is perverse ,who can fathom it? (Jer. 17:9).

Reading from the Masoretic,the BLB uses the wrong word in Jeremiah 17-9

The word in Jeremiah 17:9 (aleph-noun-shin) is not the same as the word used in the other verses in Jeremiah (aleph-noun-waw-shin).Jer 15:18, Jer 30:12, Jer 30:15

Check Genesis 18:16 in the BLB, which translates the plural of aleph-noun-shin as “men”, but has the wrong word in the lexicon/concordance. You can’t see the error unless you check the Masoretic for the relevant verses.

Pronunciation is a shibboleth, aleph takes the vowel sound of the letter(s) adjacent to it, which is enash and not anash.

The Hebrew word enash [???], doesn’t mean “incurably sick”, it means people, or beings, perhaps in a social sense. Eysh [???] = male, Eshah [???] = female. The word for sickness is enowsh[????], eg Jer 15:18, Jer 30:12, Jer 30:15

Perhaps this is the accurate rendering?

The heart is deep beyond all things, and it is the man, and who can know him?

Brenton Greek Septuagint (LXX, Restored Names)

Perhaps this is where it comes from >

http://www.hebrew4christians.com/forum/viewtopic.php?f=151&t=1031

The Targum of Jonathan says:

Quote:

And Adam knew his wife again, at the end of a hundred and thirty years after Habel had been slain; and she bare a son, and called his name Sheth; for she said, The Lord hath given me another son instead of Habel whom Kain slew. And to Sheth also was born a son, and he called his name Enosh. That was the generation in whose days they began to err, and to make themselves idols, and surnamed their idols by the name of the Word of the Lord.

The Targum of Onkelos says:

Quote:

And Adam knew yet his wife, and she bare a son, and called his name Sheth; Because, said she, the Lord hath given me another son instead of Habel, whom Kain slew. And to Sheth also was born a son, and he called his name Enosh. Then in his days the sons of men desisted (or forbore) from praying in the name of the Lord.

These examples show the homograph translation issue / confusion well — thanks for them!

What about Caleb? I heard that it means ‘dog’ and that he is therefore a type of the gentiles sharing in the inheritance.

keleb means dog. The name “Caleb” is vocalized differently, but is considered to be a form of that root. “Dog” has both negative and positive connotations (the latter = a faithful watchdog). The lemma occurs a few dozen times in the OT, and is not specifically used as a substitute for “Gentile”. I looked them all up and don’t see any clear examples of that.

Your article Mr. Heiser was both concise and respectful, I give applause.

In respect to Mr.Missler, I do not subscribe to the bible code, or any cryptic hidden code of like manner in the text, but the man gives a good bible study!

I have a question concerning “inspiration” of the Bible.

What level of inspiration do you consider the Bible to be? Is it the inerrant word of God, or is it men defining for the reader the truth of the their daily experiences?

Im confused on this, in other words I seek a Biblical Scholar’s brief explanation. Or if you have a article you wrote already detailing this, you can post a link and I can check it out.

Thanks!

This is actually a question of authority (as worded). The Bible presents itself as authoritative revelation, both for the people of God and the unbeliever (who will be judged by its content). It’s not someone talking only about personal experiences.

I concur, much obliged.

you’re welcome