I am presuming that most of you have given Friedman’s Chapter 2 (from Who Wrote the Bible?) a read-through by now. I wanted to post a couple quick thoughts on why his description, though accurately describing the theory, actually makes me suspicious of the approach. For our purposes here, I’m not going to get into technical rough-and-tumble. Just simple items that, for me, raise red flags as to the coherence of JEDP.

Friedman’s Overview

First, Friedman notes that Genesis creation accounts in Gen 1-2 are actually two creation accounts. The bases for this conclusion are:

- A different order for creation elements.

- Different vocabulary for God (Elohim vs. Yahweh)

He then notes that the same distinction between the names for God is seen in the flood story, and so that story must be two separate stories as well, woven together by someone.

Second, E turns out to be two sources itself as well (E and P). While P also uses “elohim” for the name of God, P has several distinctive markers, namely unique vocabulary that reflects priestly concerns (sacrifice, incense, purity) and shows an interest in dates, numbers, and measurements.

To illustrate how the separate source hypothesis is valid, Friedman proceeds to illustrate J and P comprise the flood story. They can be read separately as coherent stories. The J flood story of course uses Yahweh for the name of God, while P uses Elohim.

Some Inconsistencies

Even at this stage of exposure to the theory a careful reader should notice some inconsistencies. Notice how P features oddly show up in J:

- numbers and date calculation (Gen 7:3-4, 10, 12, 17; 8:6, 12) — it’s unclear how J has “no concern for dates and numbers” when these verses are assigned to J.

- clean and unclean animals (i.e., purity concerns; Gen 7:2; 8:20) — “clean” is an important distinction for sacrifice, which J is not supposed to care about.

Of course, the response to these sorts of outliers is “Well, those inconsistencies are present because they are the work of the redactor (editor) who put the sources together.” And so we have it. Actually, that response is a classic instance of assuming what one needs to prove. And that sort of logic is found throughout the JEDP discussion. It’s coherent and neat except where it isn’t, and when it isn’t, we defer to (or blame — see below) the redactor.

My personal favorite among the inconsistencies is harder to detect, since Friedman gives such a small sampling. He insists that J uses anthropomorphic language for God but in P this quality is “virtually entirely lacking” (p. 60). Friedman is actually stronger on this denial of anthropomorphic language in P in his more academic treatment of JEDP in the Anchor Bible Dictionary. In his article on the Torah you’ll read this assertion:

“Blatant anthropomorphisms such as Gods walking in the garden of Eden (J), making Adams and Eves clothes (J), closing Noahs ark (J), smelling Noahs sacrifice (J), wrestling with Jacob (E), standing on the rock at Meribah (E), and being seen by Moses at Sinai/Horeb (J and E) are absent in P.” (ABD VI:611, R.E. Friedman; my emphasis).

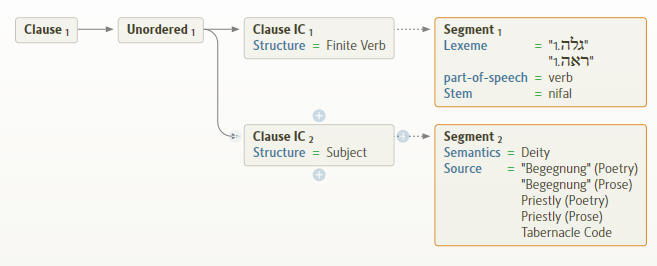

The problem is, Friedman is simply wrong here. It took me about five minutes to come up with the query in the Andersen-Forbes syntax database of the Hebrew Bible to test his assertion (I wrote a paper on this topic a couple years ago for a regional academic meeting). For those who know some Hebrew, I should explain how my query was formed. The part of his quotation that struck me as suspicious was his notion that in P the anthropomorphism of being seen (Friedman uses the example of Moses at Sinai, J and E) are absent in P. In the query I asked for all the places in P where a deity is the subject of Hebrew galah and ra’ah in the niphal (both mean “to appear” or “be seen/revealed”). Here’s what the search looks like in Logos 4 (note how the Andersen-Forbes syntax database contains searchable source-critical tags (J,E,D,P and others) and searchable tags for noun semantics (Subject: “deity”).

The results of the search uncovered clear instances in P of exactly what Friedman says isn’t in P. Here is the paper I read at that conference in case readers are interested.

The Point

What we have at this juncture (two posts on JEDP) are some issues that I think significant with respect to the some of the basic ideas that led to the source-critical view of the Pentateuch centuries ago:

1. (First post): Nearly 100 instances where two Hebrew source texts disagree as to the name for God (Yahweh or Elohim). If these textual variations were swapped in and out, there is no doubt the neatness of the name criterion for sources would be marred.

2. P verbiage and concepts showing up in J’s version of the flood story.

3. A criterion for P (no anthropomorphisms) not being valid.

Now, lest I be misunderstood, I am not claiming that the above destroys JEDP. That would be greatly overstated. Just because these criteria either fail or are not as neat / coherent as one presumes when reading about the theory doesn’t mean the theory is junk. It has other elements. (And we will look at those). What I’m saying is, here are some reasons I don’t trust the theory and wonder if there isn’t a better way to think about the authorship of the Pentateuch — one that doesn’t default to “Moses wrote every word” (something readers know I don’t believe either1). Maybe Gen 1-2 are the way they are for some other reason — literary, perhaps. Maybe one of the creation accounts is from a different author — but is that justification for seeing it as part of a very large source that runs throughout the Torah? As we’ll see, there is a good bit of circular reasoning and extrapolation within the JEDP theory. More reasons to distrust it. I just don’t like theories that over-promise and under-deliver.

And in case someone is wondering I did actually bring up some of this stuff in a course while in grad school. Specifically, I asked about the textual differences between MT and LXX with the divine names, and how that might undermine *that* single element of the theory. Believe it or not, the answer I got was “the editor was just sloppy.” Seriously? So, we’re supposed to breathlessly marvel at the skill of the editor (remember, he was so good it took painstaking work during the 18th and 19th centuries to tease out the sources), but then when there is a problem for justifying the source division we call the same guy a bungling doofus. That’s just self-serving illogic, not an answer to the question.

It just doesn’t build confidence in the approach. And there’s more.

I have an alternative explanation for the two creation stories that everyone I have told on the internet hates.

Maybe G-d wanted tofind a mate for Adam, so He created the animals a second time. This time Adam was to choose a mate from the animals as weird as this sounds, but he did not pick one, so G-d made the woman from his rib. The animals in the garden were different since the snake had legs and could talk, so maybe the other animals were different too. The first creation was for their own kind, but not the second one.

Also, I don’t think Genesis 2:19 says G-d brought the animals to Adam to name them, but to see what he will declare is for him (for Adam), and whateve he called his, G-d gave it (verb sin yud mem) a living soul. Maybe this is how some domesticated animals came ito existence.

I have told these ideas many times on the internet and I know you will laugh at them, but I will try anyway.

Kenneth Greifer

Yep; I’m not buying it either, but I didn’t laugh (really).