I think this will be my last eschatology post in regard to listing things that have no clear answer or closure. I’ll do one more where I sketch out my basic thoughts on eschatology (I can’t use the word positions, since I don’t care about the subject very much).

For this post, here’s the “not self evident question”: Is the book of Revelation to be read from start to finish as a chronology of the end times — read as a linear chronology — OR, do major sections of the book “reiterate” each other in a cyclical way (referred to as “reiteration” or “recapitulation”)?

A sub-question to the above is: Why would it matter?

As far as the first question, this one is hard to illustrate. The least complicated explanation to which I have access comes from the College Press NIV Revelation Commentary (the boldfacing us mine):

Notice that the vision contains two main elements: First, there is a revelation of the presenta revelation of what is now. The present, of course, refers to what is now from Johns perspective. Christ offers John a vision of the late first century a.d. in Asia. Second, the Lord promises a revelation of the futurea vision of what will take place later. Again, this is the future from Johns point of viewthe period from a.d. 9596 through Christs return and the consummation of the kingdom of God. Which part of the book reveals Johns present and which part reveals the future? John treats these two subjects in the order in which they are mentioned. His discussion of the present appears in 2:13:22 and takes the form of seven letters to the churches of Asia. This part of the vision describes the present circumstances of the Asian churches from Christs point of view.

The Lords revelation of the future appears in 4:122:6, as the structure of the passage makes clear. The first verse of this section (4:1) reads: After this I looked, and there before me was a door standing open in heaven. And the voice I had first heard speaking to me like a trumpet said, Come up here, and I will show you what must take place after this. The initial phrase After this, in and of itself, marks a transitionthe end of one discussion and the beginning of another. Christ then introduces the next major portion of the book when he says, I will show you what must take place after thisthat is, after the present described in chapters 2 and 3. Revelation 4:1 marks the beginning of the promised vision of what will take place later. Where does the vision of the future end? After a long series of images we come to Revelation 22:6: The angel said to me, These words are trustworthy and true. The Lord, the God of the spirits of the prophets, sent his angel to show his servants the things that must soon take place. This verse marks the end of Johns discussion of the future. The remainder of the book (22:721) consists of a short Epilogue.

By far the largest portion of Revelation describes Johns vision of the future (4:122:6). How has the author structured this important part of the book? The revelation of what will take place later begins with an introduction (4:15:14) in which John describes his new vantage point in heaven (Come up here, and I will show you). The prophet will see the future from Gods point of view. The rest of the section (6:122:6) contains the revelation of the future itself. However, a careful reading shows that John does not receive one long, sequential vision of the future. Instead, he receives three separate revelations of the complete future from Johns time through the consummation of the kingdom of God.

John describes how the future unfolds in 6:18:1. Then he starts over and describes the same period again in 8:211:19. Then he reviews the same period a third time in 12:122:6. The approach is cyclical, with each vision examining the future from a slightly different angle, and the third vision offering the most detail.

Christopher A. Davis, Revelation; The College Press NIV commentary (Joplin, Mo.: College Press Pub., 2000), 76.

This selection (I think) explains the view of the author (and most commentators on Revelation), that the book’s “future sections” repeat one another.

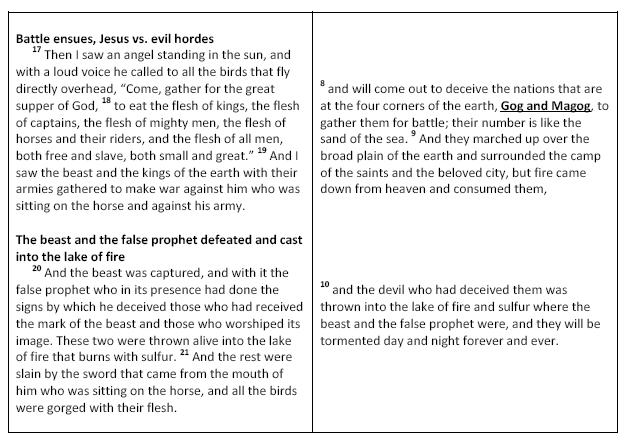

The reason the issue is important can be illustrated from one portion of the repeated cycling. Put simply, if Revelation 19:11-21 is reiterated in Rev 20:1-10, then there is no millennial kingdom. What follows will appear bewildering, but just observe the structuring and the gaps then see my notes at the end. This will illustrate how an amillennialist uses the fairly obvious reiterative structure of Revelation 4-22 to argue against a literal 1000 year millennium. Stay with me.

A few observations are in order.

1. There are certifiable connections between the second and third sections.

2. The table on the right does *not* repeat the second coming just Armageddon and its aftermath.

3. The above means that as assumed equation between the period before the second coming is to be struck. The lefthand column has nothing but by implication the age before the second coming = the church age. That would mean, when bringing the right column into the picture, that the church age of the left corresponds to Rev 20:1-7, the description of the millennium. Therefore, church age = millennium talk of Rev 20. The church IS that kingdom age.

Now, at this point, if youre a premillennialist, youre thinking good grief this is contrived and self-serving. I understand. But did you notice I have Gog and Magog underlined? That reference is actually the key to the whole idea the justification for what looks like interpretive gymnastics.

But how? Very simple.

1. Ezekiel 38-39 describes the Gog and Magog battle.

2. In that description, there is a reference to the birds being summoned to devour the flesh of Yahwehs defeated foes (39:4, 17-18). (Followers of my divine council work will note the reference to the bulls of Bashan in v. 18 just notice it not going to comment on it here).

3. This birds devouring the flesh of the Day of Yahweh victims is the only such reference in the OT. As such, it must be what was in Johns mind when writing Revelation 19:17-19. Got it? Now heres the kicker

4. The fact that John explicitly references Gog and Magog in Rev 20:8 shows that JOHN intended Rev 20:8-10 to be a repetition of Rev 19:17-19.

5. If we agree with number 4, then the structural synchronism falls into place and the millennium = the church age.

Bear in mind that this is one of the more explosive reiteration sections. It is NOT the only such section that an amillennialist will note in defense of his/her position. There are others. What I want premillennialist readers to get is that they ought to stop saying the amillennial view is the result of spiritualizing the text. The amillennialist has very clear exegetical arguments. If one begins with Galatians 3, which clearly has believers (the Church) as the inheritors of the Abrahamic covenant promises, and then follows with this textual appeal to the precise wording of Ezekiel 38-39, they aint sucking it out of their thumbs. But that doesnt mean it isnt without weaknesses some serious ones at that.

So how do premillennialists escape this? Well, theres the ridiculous strategy of saying that Rev 20:8 reference to Gog and Magog must be a second Gog and Magog event, not the one in Ezekiel. Thanks for that invention please patent it. This is nothing more than simply adding an event to the Bible to make your system work. But prophecy experts do it all the time, even in print. If you favor this argument, you should stop reading this blog and look for the newest end times novel in your Christian bookstore and just go with that.

For a more intelligent strategy, see this critique of the amillennial position.

Again, my goal is to get you to see the thinking processes so you can avoid pretending anyones view is self-evident.

Quick question-and maybe I’m misunderstanding your post here-are you saying that amillenialists view the 1000 year period in the right hand column (where satan is bound up, etc.) as figurative of a church age? I can kinda see that part as far as satan and his demons being subject to the authority of Christ during the church age…but the other where it says the dead come to life and reign with Christ (Rev 19:4-5) how could that be happening during the church age?…Please let me know if I’m tracking, your first point #3 seemed fuzzy to my brain and I got a little lost there, I wish I could see it reworded…but maybe it’s just the 1:10 a.m. factor. Agree with that last sentence,btw!

yes; you need to ask an amillennialist. The reigning with Christ could be construed as being with/in Christ even at death. Makes little sense to me, but there you go.

Your not interested in the Eschaton, or not interested in formulating a rigid view/position ?

nope. I’ll list of few “I believe this or that” items with respect to eschatology. but it’s pointless to have much rigidity in an area where there is so little clarity.

Tthis paper by Beatrice S Neil, highlights the the escalating of the warfare between Christ and satan in the repetitions of the verses 19 & 20, theorfore putting the argument that it should be considered a sequential reading rather than a reiteration. I found it interesting, maybe someone else will.

http://www.auss.info/auss_publication_file.php?pub_id=1101&journal=1&type=pdf

Thanks Mike!

Thanks Nobunaga for the PDF

No problem Bloop2000, just to give a heads up it seems to be a SDA paper although it doesnt concern the controversial SDA doctrine, i feel i have to say that. I go to a Reformed Presbyterian Church so i dont support SDA in any way but as a Reformed Christian even the Catholics get some things right so why cant the SDA. (joke) No Denomination has perfect theology.

I found the case for reading Revelations in a progressive way to be interesting. Just dont tell my Minister.

just a thought…is there any way it can be both linear and cyclical? Because I can see bits of both as opposed to one overarching view.

sure – no need to pick

e.g. I read this quote online from a book called The Wrap-up by Kay D. Paulson

“That the seals, trumpets, and bowls are somewhat cyclical in structure and content is evident in that all three seem to cover the scope of end-time events. Also, all three end in severe disturbances on earth and in visions of the redeemed before the throne in heaven. Yet the seals, trumpets, and bowls are also somewhat linear in that the magnitude of devastation swells with each succeeding series and each series extends further toward the final consummation of all things in Christ.”

Also, since we are seeing this from God’s point of view (come up here) and He is 3 in 1, could the 3 seven-fold groupings (seals,bowls,trumpets) be representative of His own nature and perspective? i.e. as He is 3 persons in community yet one, and as his spirit is seven-fold (symbolizing perfection and wholeness)…*could all these events be happening simultaneously on earth…rather than sequentially? I mean, from God’s point of view (perfect, time as a whole; end from the beginning *not linear*) this whole “series” of cataclysms premillers attribute to 7 years could just be one day…The Day of the Lord. (Heck, it could last 1000 if we took Peter literally, lol,…how’s that for wrath?).

p.s. I realize this would only work if you hold to the God’s outside of time belief (which has been addressed in other blogs here) as I do.

yes, and the “God outside of time” has problems. Probably the best (but I can’t call it uncomplicated) explanation of the problems with that are put forth by William Lane Craig here: http://www.leaderu.com/offices/billcraig/docs/eternity.html (See Craig’s collection of articles on this here: http://www.leaderu.com/offices/billcraig/menus/eternity.html).

To clarify I can see the 3 seven-fold groupings as different aspects of a single day (whether a 24 hour day or a “god day”)…point is the series of visions may stand in for all the events God has planned to unfurl at once rather than over a period of time. (If you fill a cup to overflowing–a symbol used in describing God’s wrath–it doesn’t just overflow over one side of the cup for awhile then another then another…it overflows at the same time around its circumference…all the judgments could blanket the earth the same way).

I prefer what I call the telescopic view. The three sections overlap but each succesive section gets more detailed. The above quote makes complete sense to me:

‘The rest of the section (6:122:6) contains the revelation of the future itself. However, a careful reading shows that John does not receive one long, sequential vision of the future. Instead, he receives three separate revelations of the complete future from Johns time through the consummation of the kingdom of God.

John describes how the future unfolds in 6:18:1. Then he starts over and describes the same period again in 8:211:19. Then he reviews the same period a third time in 12:122:6. The approach is cyclical, with each vision examining the future from a slightly different angle, and the third vision offering the most detail.’

There are grammatical and structural clues that I think seal this interpretation – pardon the pun 🙂

Just as an example Chapter 6:17. Why would the people being crying out that the great day of His wrath has come if it is still yet future. This is suspposed to be at the begining of the tribulation according to the linear view yet after the sixth seal. I think simply this is the time just prior to the return of the Lord. John then backs up and goes through it again in more deatail starting with the seventh seal which is really 7 trumpets – and so on.

Good reads.

A question for ‘Nobunaga”, you said, “it seems to be a SDA paper”.

What is “SDA”? Maybe I should have read things more carefully.

SDA=seventh day adventist.

SDAers are, in general, fairly serious people about the bible…until they get to ellen g white. When reviewing their stuff, that should always be in the back of ones mind.

Thanks for the link nobunaga

J. Molina, I found your perspective (e.g. three in one and seven spirit) to be very interesting. Any lit on this? I don’t know why this hasn’t been obvious to me…but then prophecy is never obvious, eh? This whole blog has been mind blowing overall. I came in a naive premil sort, but think I might exit an amillenialist…or a who cares mellenialist. I look forward to rereading this section a few times. Keep the comments coming as they are enlightening.

Although I am not an A’ nor Pre’ milleniialist, I am however a firm millenialist in general. There is more evidence outside revelations (albeit somewhat circumstantial) for an actual 1000 year reign then in the last book itself. Peter in his letter connects judgment day with a thousand years, which follows after the Lord’s wrath. There are several mentions of a resurrection upon Christ’s return (just and unjust in the same day btw). It must be physical as Paul tells us. Also following framework of the Feasts of the Lord, as He did with Passover at His death and resurrection. There is a ten day gap between the start of Trumpets (symbol of the great trumpet blast), to Atonement (symbol of the scrolls being sealed up and judgment cast). Couple days later Tabernacles, when God comes to dwell with us. These are not revelation only symbols, those symbols are taken from the very Feasts celebrated to commemorate those coming events. I think amillenialists poopoo that by using replacement theology. i.e. the church is the new Israel, in which I say “just try claiming that right, see how far that goes”.

@drmaryann I wish I could tell you there was lit on this but honestly after I read the quote I posted–and having had my brain saturating in an explanation of the Trinity from the book “The Reason for God” by Timothy Keller–it kinda just leaped out at me and made sense. Thanks for finding my idea interesting though!

@MSH Yes, I remember that the view has problems, I look forward to revisiting this (it was a good topic when you did a bit on it)…I just thought it illustrates better what I was trying to say that time doesn’t relate to God as it does to us and so the whole perspective aspect of Revelation comes into play (it’s a vision given to John *from* heaven’s balcony sort of speak using symbolic language that through its use of numerical imagery invokes the mind and person of God…not the perspective of man and should be viewed as such imo). John just relates what he sees, he never interprets (which I find interesting) in fact, the angels do some interpreting but not John. Not to say it can’t be understood from man’s perspective, of course.

I’ve been watching videos on Youtube with Michael discussing eschatology and the sons of god, especially the area where the tribe of Dan settled– Bashan. I’m not sure if there is anything to this, but I’ve noticed that Og is the king of Bashan. So, is this relevant to Gog and Magog?

not directly; indirectly in terms of the “foe from the north (tsaphon)” concept. See the Unseen Realm for that material.