Readers may recall my series way back when on “Why an obsession with eschatology is a waste of time.”1 In that lengthy series, I noted (somewhere) that one of the major issues separating any “literalist” millennial position is that Israel still needs to inherit the Promised Land. Yes, so the argument goes, while it’s true that the Church has inherited the Abrahamic covenant in Galatians 3 (see esp. vv. 26-29), that chapter doesn’t mention the land part of the promise. And so we must still expect that the land element still needs fulfillment. 2 This interpretive logic chain is of course disputed by amillennialists. One reason this is so is illustrated below (the land element was already fulfilled and Israel lost its national claim in the exile – which itself has some coherence problems, but I digress).

Tied up in all of this is an issue that I’ve honestly never seen a popular “prophecy teacher” address: the fact that Scripture itself does not give a unified picture of just what is meant by the land promised to Israel and what it geographically entails. There are actually three descriptions given in the Old Testament for that, and they don’t precisely overlap. And then there is the issue of the tribal allotments. They also have some imprecisions in regard to allotted land that doesn’t seem to nicely fit within overall descriptions of the land promised to Israel and (the reverse) unallotted land that lies within those descriptions. (See the first image below).

There’s an excellent article on this subject: Zecharia Kallai, “The Patriarchal Boundaries, Canaan, and the Land of Israel: Patterns and Applications in Biblical Historiography,” Israel Exploration Journal 47, 1/2 (1997):69-82. Unfortunately, I can’t post it due to copyright restrictions. I can only excerpt it. Here’s how it begins (pp. 69-70):

Among the issues pertaining to the Promised Land, perhaps the most perplexing is that of the patriarchal boundaries, set forth in the covenant of Abram (Gen. 15:18b). The promise of the land occupies a central place in the ideology of ancient Israel due to the notion that the acquisition of, and right to possess, a country are due to divine intervention.

The major problem is the intimate relationship of these boundaries to those of the Promised Land, notwithstanding an indubitable territorial disparity between them. A clear territorial distinction must be drawn between three concepts: 1) the patriarchal boundaries; 2) the land of Canaan; and 3) the land of Israel (Fig. 1). Of these three, Canaan is the Promised Land, while the land of Israel, despite its partial territorial divergence, is the realization of this promise. The patriarchal boundaries, however, although closely linked with the promise of the land, patently differ from the other two delineations. Defining their respective territorial outlines and ascertaining the associated patterns and formulae which express and intimate these concepts will clarify their several historiographical functions.

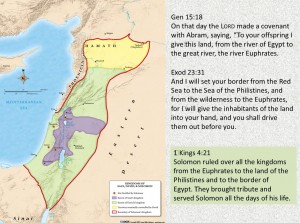

Here is “Figure 1” alluded to in this excerpt (click on the map for a larger view):

Of the many interesting things about the boundary situation (which is very complicated), two are fairly simple to understand and, therefore, illustrate the problem for all those so sure about the issue and its application to prophecy. First, are the coastal areas of Tyre and Sidon (Phoenicia) are included in what is Israel’s? Second, are the lands of the Philistines included? The map reflects the ambiguity of the first, but includes the second within Israelite territory (Gath, Ashodod, Gaza, Ekron, Ashekelon were the five Philistine cities. Now for two brief observations.

In regard to Tyre and Sidon, if they are NOT to be included (but see Josh 11:8; Josh 19:28-29; Judg 1:31), then it certainly appears that ALL of these lands (not how this image encompasses the divergent descriptions and boundaries illustrated above) were indeed inherited by Israel in OT times – meaning one could argue coherently that the land promise was fulfilled. This was in the days of Solomon. This is the basis for an amillennial claim that the land element was already fulfilled and lost, so Paul didn’t need to mention it in Galatians 3. Note the map and the passages (again, click on the map for a larger view):

In regard to whether the Philistine cities were to be included, you’d think that would be clear. But then you run into verses like Joshua 11:21-22 –

21 And Joshua came at that time and cut off the Anakim from the hill country, from Hebron, from Debir, from Anab, and from all the hill country of Judah, and from all the hill country of Israel. Joshua devoted them to destruction with their cities. 22 There was none of the Anakim left in the land of the people of Israel. Only in Gaza, in Gath, and in Ashdod did some remain. (ESV)

This verse reads as though “the land of the people of Israel” does not include the Philistine cities. If it did, then the verse appears contradictory and erroneous – how could it say there were no Anakim left in Israelite land when there were? When you really drill down into the land issue (like Kallai in his article), you find these sorts of things. Yeah, it’s boring reading boundary markers in the Bible, but they have obvious importance here.

This is the sort of stuff that real scholars are aware of and struggle with. Though the land talk is fundamental to much of what the popular prophecy pundits say (and their incomes), I won’t be holding my breath that they’ll ever go here and say anything meaningful. If any of them are reading this, it’s likely the first time they’ve ever encountered any of it.

Mike,

I contend the land (regardless of specific boundaries) is still important. It seems to me that this “day of the Lord” is a future event:

“For behold, in those days and at that time, when I restore the fortunes of Judah and Jerusalem, I will gather all the nations and bring them down to the Valley of Jehoshaphat. And I will enter into judgment with them there, on behalf of my people and my heritage Israel, because they have scattered them among the nations and have divided up my land,”(Joel 3:1–2)

“Those days ad that time” are described just above at the end of chapter 1 and it seems unimaginable that those events occurred in the past. This means there is a future judgment for those who divide up Israel’s land.

This is only true (and of course it might be) if what is said in the great commission, and what happens in Acts and the ministry of Paul, does not create a hard and fast equation of “the land” to “the world.” If “my land” is the whole world in God’s eyes (as opposed to just Israel), that changes everything. That question is, as I’m sure you can tell, tied up with the “who is Israel?” question (all believers a la Galatians 3, or does Paul’s use of “Israel” elsewhere – cf. Rom 9-11 – allow for an ethnic/political/national meaning that runs in parallel to “Israel = all believers”?) That’s the hard part / iffy part. Eschatological coherence (not to mention certainty) rises and falls on these issues. We all have to guess at some point. Anyone who pretends they know with certainty either doesn’t have a grasp of these issues or is self-deceived (or lying).

It’s just not that iffy to me but I suppose it depends on one’s hermeneutic. It’s not so much the idea of a literal interpretation, but it is the approach as in does one approach the text inductively from Genesis forward or deductively from the fulfillment backward. Does the inspired authors’ intent for his original readers take precedence or does a later context (foreign to the original) trump the author’s context. I don’t find the reverse deductive hermeneutic to be sound. It’s one thing when an inspired NT author does it but it is all together different when a modern supercessionist does it. I don’t think they have license to override the inspired author’s intention in a passage like Joel 3.

It’s not about literalism (or not). Paul says what he says really plainly in Galatians 3 (and that’s just one example). The issue (for this comment string) is biblical usage (its wideness or narrowness and, if there is variability, how one knows which usage is happening in which place – and how “sure” one can be about that decision).

Not sure how that addresses my point? I said it was not about literalism but rather hermeneutics. I think imposing Paul’s context in Galatians onto Joel’s oracle from 600 years prior is bad form. The inspired author – Joel- had something in mind when he wrote “Israel” and “land” and that should dictate our understanding not a context 600 years later that is foreign to Joel. Author’s intent trumps later theological presuppositions.

Not when both authors are inspired; you sound like Paul doesn’t count.

“you sound like Paul doesn’t count”

I don’t see how it is valid to argue Paul’s context works backwards 600 years to redefine the term “Israel” to mean something alien to Joel’s audience. It seems like circular reasoning too.

Paul informs us that Israel (God’s family) really means believers (and it seemed it did in the OT, too – otherwise you have elect idol worshipping Israelites. I think the OT and NT are actually consistent here, and Paul gives us clarity on it.

I explained it in my original response = induction vs. deduction. Yes Paul is also inspired but Paul did not write the book of Joel, so Joel’s intention for his readers should determine the meaning not Paul’s.

Paul gets to interpret Joel in the *progress* of revelation. Otherwise you have to say Paul is wrong. I’ll channel Elliott Johnson here from my DTS days: “a prophecy can mean more than originally intended [by the human author] but it can’t mean less.”

But Paul did not interpret Joel explicitly concerning the land.

Come on, Cris – didn’t you learn any covenant theology?! 🙂 The covenantalist would say he didn’t need to – it was either already accomplished/fulfilled or *national* Israel sinned it away. (I file that under the “maybe” category). And it wouldn’t matter if Paul saw the Great Commission widening the promise to the world – there’d be no point to mentioning one little slice of land in relation to Abraham’s seed by faith – since they will inherit the world.

Covenant theology seems contrived to me. It goes back to my original comment, do you start with the fulfillment read backwards to deduce the interpretation or do you read the Bible forward inductively. The former seems circular and forced.

I read the NT as an inspired commentary on the OT. All of the systems are contrived. I see things going on between the testaments that make the content consistent – I don’t read it as a modern person, and no one in the NT was doing exegesis the way it’s taught today. They used a variety of hermeneutical approaches, including midrash. I let them do that instead of putting them in the modern box I prefer. They are tracking concepts, metaphors, symbols, words, phrases, etc. — at different times or all the same time. The NT writers didn’t approach the OT like modern evangelicals do. Consequently, I let them do their thing and enjoy it.

I think we have reached an agreement 🙂 I suppose I find my view somewhere in the tension between historic premillennialism and progressive dispensationalism.

I like a lot in those, too.

“…much of what the popular prophecy pundits say (and their incomes), ”

I’m confused. Who are these people?

You’re more blessed if you don’t know. Look up “end times” or “Bible prophecy” on Amazon and that will give you a glimpse.

Hello Professor

I would be interest in finding out more about your view on the book of Revelation in regard to the fulfilment of the Millennial Kingdom.

I too have struggled with this issue and have yet to come to a conclusion on how or if the Millennial Kingdom will unfold.

My view of the Second Coming is the Lord Jesus Christ comes back to remove Satan’s Kingdom and setup His own with the help of His Angels and the Elect who are raised from the dead, with Christ remaining here for 1000 years. The Elect from then on do not die, ever.

Then after 1000 years Satan is released and then he wages war on Christ, His Angels and His elect. Only to be defeated by Christ forever.

I still have not decided whether there is human procreation during the Millennial Kingdom.

As you see I am just trying to keep a consistent view to encompass all the Bible prophesies, both Old and New Testaments.

Is this close to your view on the final fulfilment of Scripture?

Kind regards, Alasdair Maclean

You’ll need to read through the eschatology series: https://drmsh.com/the-naked-bible/eschatology-discussion/

I don’t plan on revisiting any of that or adding to it. Prophecy (honestly) bores me.

The word, ‘prophecy’ is an abused word( First time I have felt pity for a word in my learning of language) . I need to say this again, the bible is not a book of secrets , it is not a mystery writing. In fact; it is (the absence of secrets and mystery writings) that lead me to the bible again. Land is in the bible a very contextual word. O/T and N/T.

not sure what you mean by “contextual” (the meaning of every word is driven by context).

what I meant in regard to ‘contextual words, was this: A word can be non contextual ; e.g ( lack of context ) , or contextual ( abundance of context ). Although maybe I should have worded my comments in a more coherent way. I do suppose there are varying scores of context, and that should be taken into consideration.

Blog posts critiquing Prophecy Profiteers are typically justified, since Prophecy Profiteers are obviously blinded shepherds, blinded by their own ignorance and presuppositions, knowing little of what they speak.

That said – your claim in the Eschatology series: For those just starting on these, my point is not to take any positions (I don’t); is not entirely true since you do in fact offer a position, which suggests an obsession with eschatology is a waste of time.

Is it?

Of the Bible’s 31124 (or so) verses approximately 23210 of those verses are old covenant scripture. Though 74.57% (or so) of the Bible is old covenant scripture, there are still many Christian ministers and Christians alike who argue these texts are obsolete, irrelevant, no longer necessary (because of a new dispensation); this despite [2 Timothy 3:16].

Of the Bible’s 31124 (or so) verses approximately 6641 old covenant verses and 1711 new covenant verses are predictive, prophetic and eschatological. Approximately 8352 of the Bible’s verses are prophetic which is just under 27%: and yet does it seem like a sound doctrine to be suggesting that having an obsession with this portion of scripture is a waste of time because it may be eschatological – or not understood?

It’s fallacious to suggest because scripture may not be understood correctly, it contains no valid meaning, or is not intended to be understood. Jesus spoke in parables. Why?

He suggested it so the wisdom he spoke seemed foolish to the world, while still being recognized as wise to his sheep (those the world deemed foolish), and for whom it was intended [Matt 13:11-13]. Jesus also said His sheep heard His voice [John 10:27].

How is the Bible’s eschatological content (27, or so percent) any different? Was it’s purpose mere bloat, to inflate the size of the material?

The verse [Rev 6:1] shows by the breaking of seals His revelation is progressive and temporal. God takes pleasure in covering a think, but He does not hide it for all times, as the unbroken seals attest. It is hidden so that it may be uncovered. Only a fool takes no pleasure in understanding, listening instead to his own thoughts [Pro 18:2]. The opposite is true for the wise [Pro 25:2].

So, here are a couple of reactions to your observations:

1. N.T. Wright has recently begun suggesting that Paul’s understanding of the purpose of the Abrahamic covenant reflected a theme of reconciliation between the Creator and all of creation. Accordingly Israel’s inheritance was to be the entire world, not some localized region.

Your observation that the ‘promised land’ is poorly defined is not much of criticism given the possibility of N.T. Wright’s insight. Not only, but if correct, this implies Adam and Eve’s expulsion from Ea, Eden, Earth, or wherever, would make this the first Exodus; just as it would make Israel’s foray into Assyria/Babylon the third.

Promises such as “I shall bless those blessing you, and curse those cursing you, and blessed in you shall be all the families of the earth ([Gen 12:3]) make a whole lot more sense if understood as God intending this Holy Mountain to be something to grow and fill the whole earth [Dan 2:35]. Besides, of the themes contained in the Abrahamic promise, issues of land were minor (subordinate) to other greater themes, which generally go unnoticed (such a promise made by a God who gives his glory to no other promising to give a mere man “a great name” [Gen 12:2]. Oh what a riddle!)

Also, even if the promised land weren’t poorly defined in scripture – there’s still a monster of a presupposition contained in this argument that needs validation. Don’t simply presuppose, but prove how we’re able to recognize Israel in the world today, or indeed throughout history! Twenty-five hundred years ago Israel was to forget their God, their covenant [Isa 65:11][Jer 2:32; 23:27], their language [Jer 5:15][Dan 1:4][Eze 3:4-11], and their great name [Isa 62:2]. Israel was to become blind and deaf [Isa 6:10; 29:9; 42:19] being lead into a new land, one they did not know [Isa 42:16]. Paul knew this and confirmed it happened [Rom 11:25].

When John Hyrcanus fused Edom into Judah he was converting 12 tribes of Esau into the 2.5 tiny tribes of Judah. Even the Judean King was not an Israelite but an Edomite (Herod the Idumean); thus fulfilling Esau’s reclamation of their birthright [Obad 8-11]

So, if Israel would lose themselves in history, how can we be so sure we haven’t also?

Looking at the disagreement between the Messiah and his opponents in [John 8:31-38], it’s not so clear. Yehshua/Jesus was speaking of sin as slavery, yet his opponents thought he was speaking about actual slavery. Look at what they say “We are offspring of Abraham and have never been enslaved to anyone.” What Israelite would say this? At this point in history Israel has been enslaved twice (Egypt/Babylon)!

Only Esau had never been enslaved ( ISBN: 1850752052)).

We can never say intelligibly ‘Israel has never reclaimed their land‘ if our identification of Israel is possibly or certainly false [Rev 2:9; 3:9].

With respect to judging the worth of eschatology and its fulfilment, we have to first understand what the bible means what it says. Secondly, we cannot be blinded by our own assumptions, being brave enough look beyond them (and thinking we can recognize the flock, when the bible suggests they wouldn’t be able to recognize themselves is such a presupposition).

Yes, obsessing over an issue that requires omniscience for a resolution is a waste of time.

Yes, obsessing over an issue that requires omniscience for a resolution is a waste of time. And which author’s intent? I’ll go with God on that one.

Going with God is always wise.

Perhaps I misunderstood what you meant by obsession. I took ‘obsession’ to be the continuous preoccupation with the entire word of God (including prophecy).

A rough estimation puts prophecy to be just under 27% of the bible so a position suggesting this portion of scripture was at best closed to us, at worst irrelevant would naturally illicit a response.

Your reference to God’s omniscience confuses me, and suggests I do not understand your position.

Yes, I meant “continuous preoccupation” but also making prophetic decipherment part of the gospel (as some do – “How can you really be a believer if you don’t believe X about the Lord’s return?” – those people do exist).

On omniscience – certainty with respect to correctly parsing the host of ambiguous elements that go into interpreting prophecy requires omniscience. Since I’m not omniscient, I tend not to worry about it much.

We’re agreed upon those shepherds who try to restrict ‘true believers’ to only those adhering to some particular exegesis of prophecy. In fact only by the shedding of blood is there forgiveness of sin. Belief in the efficacy of the blood of the Son of David is evidence of faith. If discernment of prophecy were the precondition of faith, few modern ministers (including the so-called ‘Prophecy Profiteers’) would qualify.

Although I agree that correctly parsing the host of ambiguous elements that go into interpreting prophecy requires omniscience, I don’t agree (with the implication) this makes it beyond modern man.

As it turns we were sent a helper [John 14:16] who possesses omniscience [1 Cor 2:11], one we can rely upon through faith.

He was sent to us not only to assist with the construction of new covenant scripture [John 14:26] but also its interpretation providing discernment to those who walk in the Spirit [1 Cor 2:13].

That most modern believers don’t boldly ask God for this Spirit of discernment, holding more tightly to ‘Father, Son & Holy Book’ rather than ‘Father, Son & Holy Spirit’ doesn’t mean that He is withheld from us.

The appeal to the Spirit is flawed. What makes you think he’s more on your side than Calvin’s or Spurgeon’s or [fill in the blank]? Are you just bolder than they were? (Of course not – and I know that isn’t what you’re actually saying – but it’s where this thinking leads).

Sincere (i.e., REAL) believers are at loggerheads on prophecy (and have been for two millennia), so the passage about the Spirit helping us is no path to resolving disagreements.

I wouldn’t presume to put constraints on what the Spirit can and cannot do. Clearly this lack of agreement you speak of suggests not everyone seeks the Spirit equally; and I only brought Him up to refute the idea that lack of omniscience on our part constitutes some type of limitation.

I doubt God gave us a book intending it to be misunderstood.

Sincere (i.e., REAL) believers being at loggerheads on prophecy does not mean some particular interpretation is correct. You raise the point appealing to the Spirit does not help. I disagree, and you do me a dis-service by crediting me with the suggestion the only role the Spirit plays is to bolster one’s knowledge claims)

At the heart of your own effort as an academic is the principle “truth bears scrutiny”. Also, knowledge presupposes truth.

So, if the Spirit reveals truth to even one, and that one boldly proclaims it (as was the case with Christ), I fail to see the Spirit has not been helpful. If others also recognize a proclamation as true, again the Spirit is playing a role.

Only by miring ourselves in the self-refuting perspective that there is no ‘truth’ is this false.

You’re right – God didn’t give us a book intending it to be misunderstood. But since the Spirit has to work with our brains (things like memory, intelligence, intuition, etc.) and not all people’s brains process information the same way, and process it according to experiences and presuppositions, which by definition can’t be the same, appeal to the Spirit is a misguided silver bullet. The NT doesn’t guarantee everyone who is in Christ (how much more of the Spirit does each person in Christ have? – They all have the Spirit equally – he isn’t renting in some people and a homeowner in others). Even in the NT Peter said some of the things Paul wrote were hard to understand. NT writers can apply the same OT passage in different ways, too. Doesn’t mean they are wrong, but the points being made wouldn’t “agree” in that sense.

The Spirit is helpful, but we are different and imperfect. Until we are all glorified, we aren’t going to be agreeing on everything. The Spirit’s solution to that is ultimate sanctification – to think you’ve got X right because you’re more Spirit led is ultimately an arrogant position, though unintentional (for many).

I expect Jesus will get all the Promised Land during His 1000 year reign on Earth and by extension the whole Earth.

Is this an eternal covenant?

Yet, after Jesus’ reign on Old Earth; the Old Earth will pass away (including the Promised Land)and the New Heaven and New Earth takes its place. Will God transfer the Promised Land to the New? (I think not.)

This of course assumes the “millenium” and the new earth aren’t the same thing. 🙂

I think its obvious they are different if you study the smaller details. Sin/Death are two details active after a 1000 years into Jesus’ reign on Old Earth; while after creating New Heaven/New Earth—which is the believer/overcomer’s inheritance—it indicates the presence of no curse/sin/death.

I understand not liking the term millennial, considering Jesus’ reign is eternal. We use millennial as a means to parse/understand what being communicated.

I know you don’t like prophecy, but a couple of the things you teach helped me recognize a simple, but different way to parse Revelation that is not so Rapture-driven. You also enhance my belief that Revelation is in chronological order.

Mike, you alluded to a question I have been struggling with lately, which is; just who is Israel? There is much back and forth with replacement theology, messianic Jews, prophecy wags, and politicians… I have to agree it gets tedious. To be fair, how you define Israel does seem to define the land question. You were spot on there.

The tribal division question doesn’t seem that developed. Does the omission of the tribe of Dan from Revelation 7 have a meaning pertinent to this discussion? Dan was known for idolatry and if I recall the land of Decapolis during the II Temple period was former Dan territory. If certain tribes are included and omitted during different periods of history does that hint at the “nature of the Land?”

Some have proposed that the omission of Dan in Rev 7 is due to Dan being the origin for antichrist – which is in turn based on the “serpent language” used with respect to Dan in the OT (Gen 49.17; Deut 33:22 [the serpent connection here has to do with Bashan – I can’t explain that in this space). The Dan-antichrist tradition has old roots, but I think it’s exegetical basis is tenuous. For instance, the Dan-Antichrist idea shows up in the Pseud. book Testament of Dan 5:6–7 and Irenaeus (Adversus Haereses 5.30.2) and Hippolytus (De Antichristo, 14–15).

Beale writes about this (more than most commentators):

“Possibly Dan is omitted because it was closely associated with idol worship (Judg. 18:16–19; 1 Kgs. 12:28–30; Targ. Pal. Exod. 17:8; Targ. Pal. Num. 11:1; Targ. Cant. 2:15; Targ. Jer. 8:16; Midr. Rab. Gen. 43.2; Midr. Rab. Num. 2.10; b. Sanhedrin 96a; Pesikta Rabbati 11.13; 12.13; 46.3; Sifre Deut. 357 on Deut. 34:1). In Targ. Pal. Num. 22:41–23:1 Dan is said to have been involved in “strange [i.e., idol] worship” and then in the latter part of ch. 23 the Targum says that “they who serve false idols are not established among the tribes of the sons of Israel.” The conjecture that a scribe mistook a supposed abbreviation ΔΑΝ for ΜΑΝ (= Manasseh) in Rev. 7:6 is unlikely because their is no ms. evidence for such an abbreviation.

Ephraim likewise may have been excluded from the Revelation 7 list because of its association with idolatry. Ephraim was noted in distinction from the other tribes for its penchant for idolatry, for which it was to be exterminated by divine judgment (Hos. 4:17–14:8; cf. Hos. 5:9). Some suggest that these two omissions could be a hint that John is conducting a polemic against a part of the professing church who are compromising through idolatry. But since these are omissions, they more likely point in the opposite direction, to an attempt to portray the professing church as apparently pure. Even though the whole church makes a profession of faith, it has become impure like Israel of old. And, as in Israel, only a remnant in the professing church will be saved. This is consistent with chs. 2–3, where the same portrait of the church is found, and with Ezekiel 9, where those marked are a remnant to be saved from the wrath coming on the majority of Jerusalem’s inhabitants. Therefore, Revelation 7:3–8 does not picture the prophecy of Ezekiel 48 and other related restoration prophecies as fulfilled with literal precision, since Dan and Ephraim are excluded (in Ezekiel 48 Dan appears first and Ephraim sixth; also Test. Dan 5:9–13 refers to the end-time restoration of Dan; the Temple Scroll [11QT 39.11–13; 40.14–41.10] also includes Dan in its end-time tribal list; for evidence that John has in mind, at least partly, the list of tribes found in the Ezekiel 48 prophecy of the restored eschatological Israel, see above on 7:3 and on 21:9–22:5). This lends more plausibility to a figurative understanding of the tribal list in Revelation 7.”

G. K. Beale, The Book of Revelation: a Commentary on the Greek Text (New International Greek Testament Commentary; Grand Rapids, MI; Carlisle, Cumbria: W.B. Eerdmans; Paternoster Press, 1999), 420–421.

Can someone please tell me the proper translation or meaning of the word Anakim? The reason for asking this is because Goliath came from Goth- one of the above mentioned places where the Anakim still endured. He was a giant and was described in Deu 2:10 and 2:11 in a similar way that the Nephilim of Genesis 6:4 are described. It has previously been theorized that if the Sons of God are not human, then one of the causes for this could be due to Satan trying to spread his own seed (or any type of seed that is not the “woman’s seed” as it is referred to in God’s promise) to prevent God’s word or promise from happening when he foretold that there would be a Promised Land. I still am not convinced by other theories about the Sons of God being human- I do not know what they may be- but human does not make sense because they would not have a race of offspring who are giants- and I am trying very hard to find the real meaning of the word Anankim in order to understand JUST WHAT EXACTLY the Anakim was – and what does that make Goliath, specifically? Becasue many people who believe that Goliath was Anakim do a search for the word “giant” and do not go any farther and assume it simply is Nephilim or the descendant of Nephilum (which does not sound illogical_ but I want to find out the truth of the matter, if possible).

Thank you…

My apologies- this is what I previously said:

“Because many people who believe that Goliath was Anakim do a search for the word “giant” and do not go any farther and assume it simply is Nephilim or the descendant of Nephilum (which does not sound illogical_ but I want to find out the truth of the matter, if possible).”

But what I meant to say was:

“….many people who believe that Goliath was Nephilim do a search for the word “giant” and….”

The short answer is “children of Anak”; there is no consensus on the meaning of “Anak”. It is likely a proper name (eponymous or otherwise). It is not Semitic, which is one of the issues. It may be a Greek loan word (ἄναξ), meaning “lord, master” – used of gods and Homeric heroes among other referents.

It may also be Anatolian / Luwian, which is the case with “Goliath” (who was from Gath, not Goth).

You don’t need etymology for what the Anakim were. Num 13 and Deut 2-3 make it clear they were unusually tall. The word ʾadam (“humankind”; cp. Gen 1:26-27) is used to describe the victims of the conquest in cities associated with giant clans (Joshua 11:14). Arba is called “the greatest man (ʾadam) among the Anakim. The generic Hebrew word for people human populations (ʿam; i.e., human populations) is also used of giant clans: e.g., Deut. 2:10 (the Emim); Deut. 2:21 (the Zamzummim); Deut. 3:1-3 (Og’s people); Deut. 9:2 (the Anakim).

Thank god there are still anakim left in all those arab lands.

Where? Can you provide us with evidence? Photoshop doesn’t count.

Those lands are getting cleared of arabs, would there be any other reason for that? I beg you not to tell me that whatever happens isn’t god’s will.

You get your wish: Whatever happens isn’t necessarily God’s will. Why? Try reading 1 Samuel 23 for starters – foreknowledge does not necessitate predestination on God’s part. Your comment also reflects a misunderstanding of the nature of human imaging, which necessitates free will.

Everything that happens is necessarily god’s will.

Where does 1 Samuel 23 come here? Foreknowledge of what? It did not occur to David that he’ll be captured, it only occurred to him that he shouldn’t stay in that town any longer. No predestination in the “prophecy”.

You’re right, I have no idea what human imaging is.

You’re not reading it closely or well. Maybe one of the other commenters will clue you in, but I’d rather have you read the material better.